Monuments In Focus: A Visual Exploration of Ireland’s Archaeological Heritage

Ireland’s archaeological monuments are tangible remnants of a wonderfully complex and captivating history. Spanning 12,000 years of human settlement, Ireland’s 150,000 known archaeological monuments form a heritage landscape that is embedded in the very fabric of the country.

These places hold great significance for communities across Ireland, in towns, villages and the countryside, providing a sense of place, of continuity and change. This heritage serves as a wellspring of inspiration for culture, literature, art, and language.

Over the past 150 years, the National Monuments Service and the Office of Public Works have taken direct responsibility for the care of some 1,000 monuments in Ireland, including our two outstanding UNESCO World Heritage Properties, Brú na Bóinne and Sceilg Mhichíl.

The photographs exhibited in this gallery highlight how modern photography may capture the essence of antiquity. Photographing these monuments plays a crucial role in documenting their maintenance, conservation, and monitoring their condition against erosion and extreme weather events.

Ireland’s National Monuments Service Photographic Archive houses a vast collection of photographs documenting the care of these monuments over the last 150 years. The earliest glass plate images offer a view of the monuments and their condition, at times appearing as distant in time as the monuments themselves. These early images serve as a vital record of their past state, a base line to allow monitoring of change into the future.

Inspired by the shared values at the heart of UNESCO, Ireland is proud to present these images as testimony to our commitment to safeguard and protect our cultural heritage for the benefit of current and future generations.

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

Click here for more information

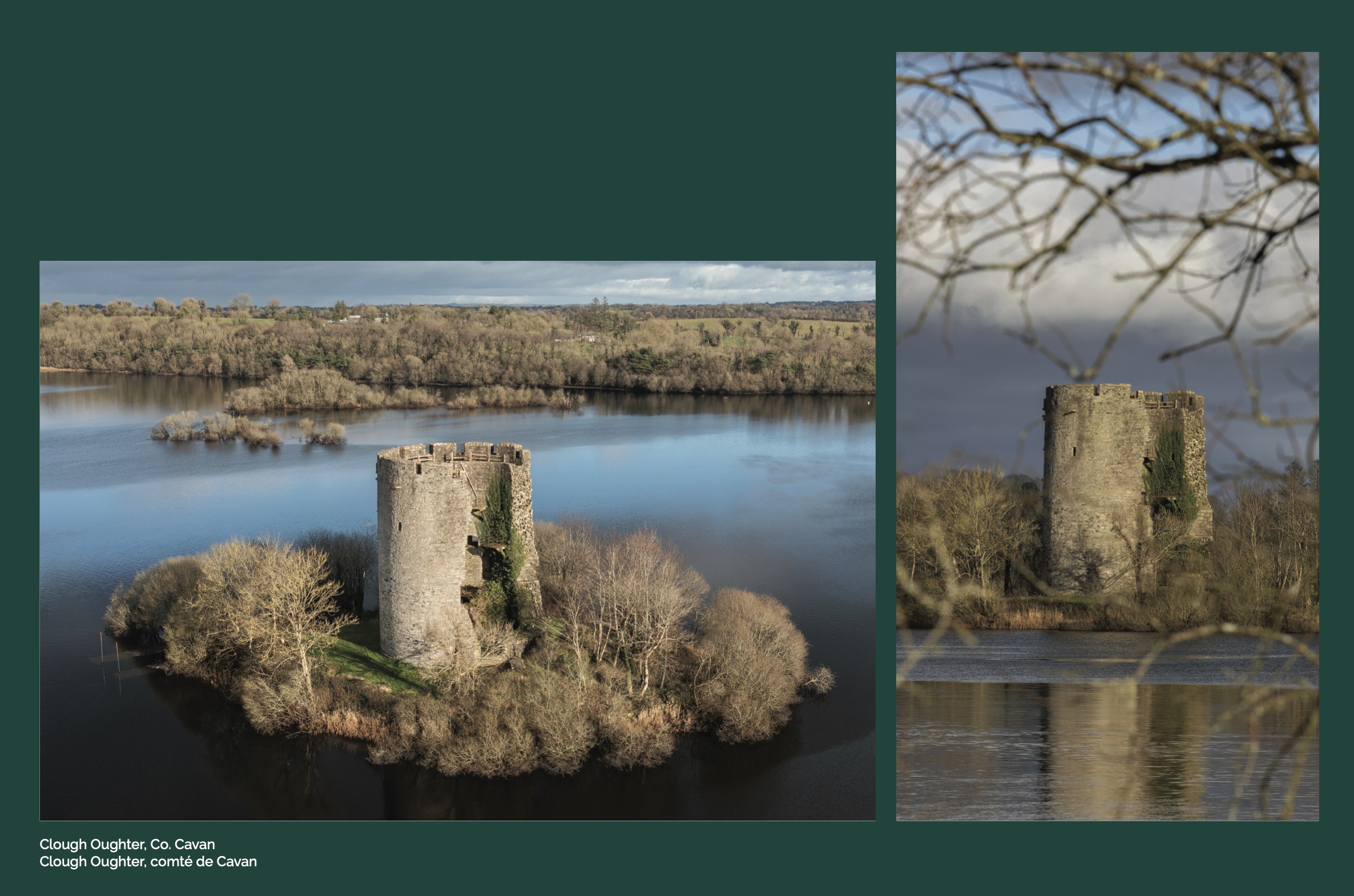

Clough Oughter, Co. Cavan

The castle of Clough Oughter, Co. Cavan dominates this tiny island in Lough Oughter, one of many lakes scattered throughout south Ulster. The circular keep is quite unusual in Ireland, and was constructed around AD1220 by the Anglo-Norman de Lacy family in their attempts to conquer new territories in the Gaelic areas that neighboured their lordship of Meath.

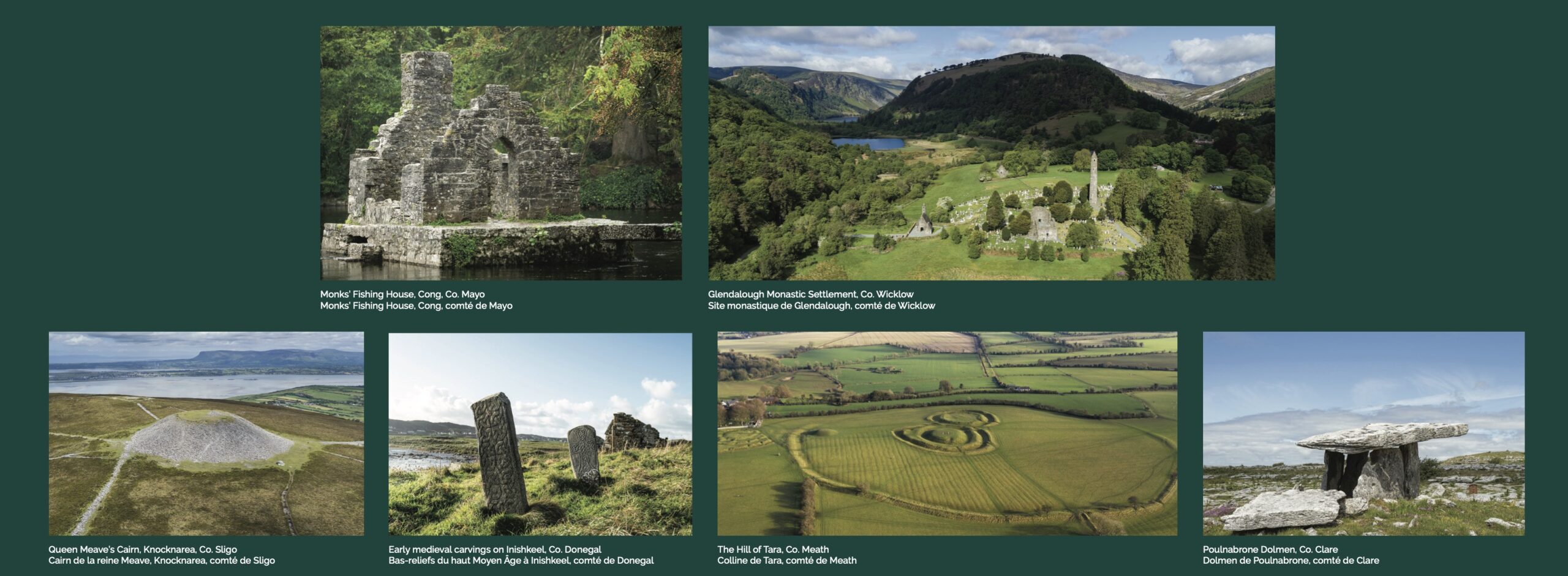

Monks’ Fishing House, Cong, Co. Mayo

Known as the Monks’ Fishing House, this small 15th century building was used by the monks of the Augustinian priory of Cong, Co. Mayo. A hole in the floor of the building allowed access to the slow-moving waters of the Cong River, near where it enters Lough Corrib, the largest lake in the west of Ireland.

Glendalough, Co. Wicklow

Glendalough takes its name from the Irish Gleann Dá Locha, which translates as the ‘glen of the two lakes’. At the end of the 6th century, a small monastery was established here by St Kevin (d. c. 620). Over time, this would become one of the greatest monasteries of early medieval Ireland. At the beginning of the 12th century Glendalough also became the seat of a short-lived diocese and a remarkable collection of churches and other buildings survive from this period.

Poulnabrone Dolmen, Co. Clare

The portal tomb at Poulnabrone, Co. Clare rises out of the limestone pavement of the Burren, a name that derives from the Irish word boireann, meaning a rocky place. Excavations found the remains of at least 35 individuals buried within the chamber, the earliest dating to 5,800 years ago during the early Neolithic period, when the tomb was first constructed.

Queen Meave’s Cairn, Knocknarea, Co. Sligo

Knocknarea is a distinctive steep-sided, flat-topped ridge that dominates the Atlantic coastline in this region. On the summit is a massive heap of stone known as Maeve’s Cairn, called after the queen of Connaught in early medieval Irish mythology. In fact, this is one of the largest monuments ever constructed in early prehistoric Ireland and has transformed the profile of the entire mountain.

Early medieval carvings on Inishkeel, Co. Donegal

These early medieval carvings are situated at an early church site on the island of Inishkeel off the west coast of Donegal. The stone in the foreground is decorated with interlace and represents the shaft of a large cross, the head of which is missing.

The Hill of Tara, Co. Meath

The Hill of Tara is host to a complex series of grass-covered earthworks, burial mounds and ceremonial enclosures that have their origins in early and late prehistory. During the early medieval period this site was recognised as the traditional inauguration place of the highkings of Ireland. In more recent centuries, Tara became an iconic symbol of Irish nationalism.

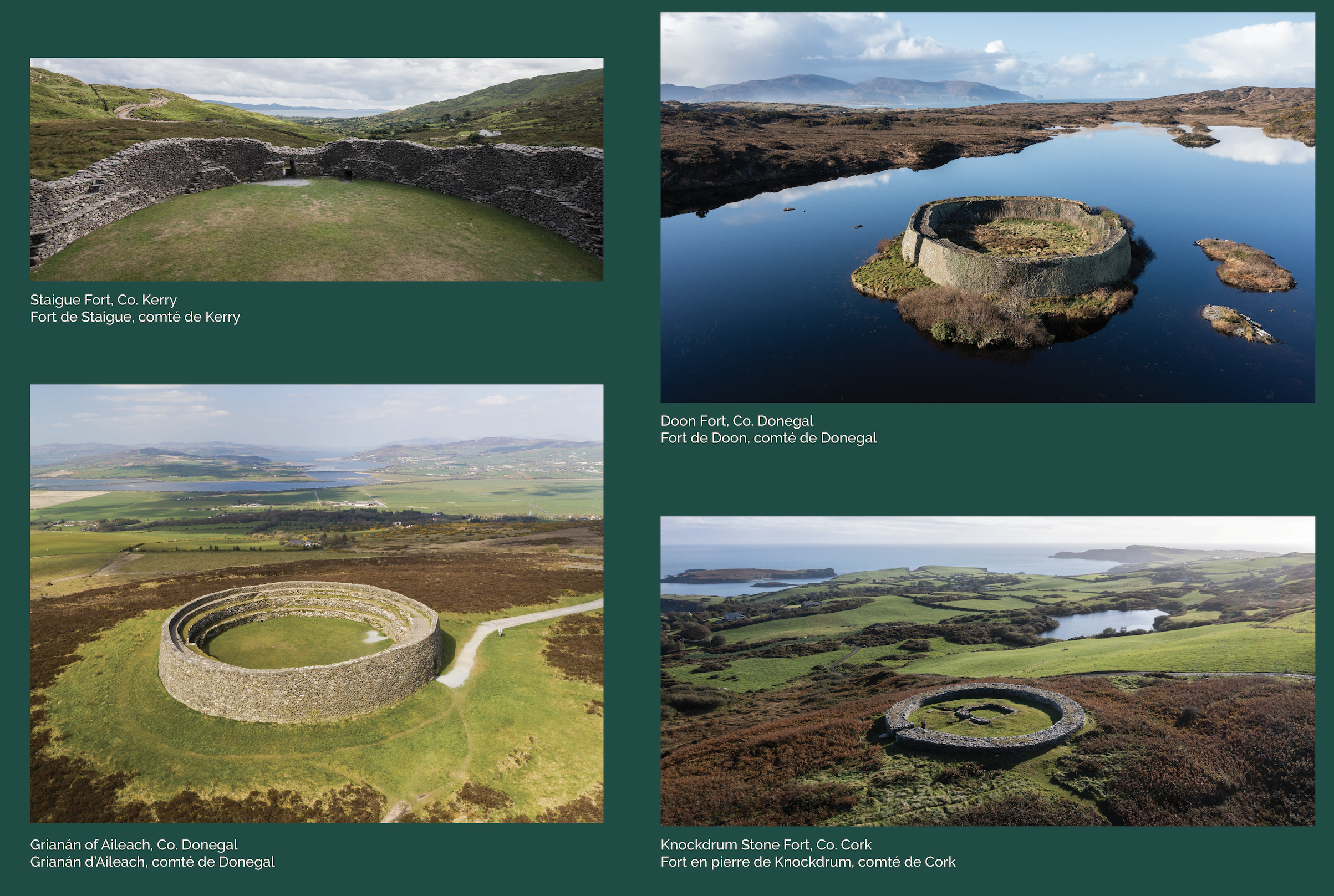

Staigue Fort, Co. Kerry

The stone fort at Staigue is nestled into the head of a narrow valley within the mountainous Iveragh Peninsula of Kerry. In contrast to the Grianán of Aileach and Knockdrum, this impressive fort was not designed to be seen or to look out over the surrounding countryside. With only a slender view down the valley towards the Atlantic, there is a definite sense that the builders were keen not to attract unnecessary attention.

Doon Fort, Co. Donegal

During the early medieval period, this small island on Doon Lough was entirely enclosed by a massive stone fort. The fort appears impregnable from the mainland, the massive walls also providing the inhabitants with welcome shelter from the Atlantic storms. The setting is truly spectacular, but unlike the Grianán of Aileach, the location here seems less about expressing political power and more about defending it.

Grianán of Aileach, Co. Donegal

It is believed that the stone fort known as the Grianán of Aileach was originally constructed sometime before AD800 by the ambitious Áed Oirdnide, king of Cenél nÉogain, a small kingdom previously confined to the Inishowen peninsula. From the summit of Greenan Mountain Áed, could view both his Inishowen homeland and gaze out over his newly won territories across the region.

Knockdrum Stone Fort, Co. Cork

Overlooking Castlehaven Bay and the coastline of west Cork, the hilltop setting of Knockdrum stone fort is reminiscent of the Grianán of Aileach. Today, its circular wall is much smaller than its Donegal cousin, but the diameter is virtually identical. Here we can see the remains of a spacious rectangular house within the walls of the fort.

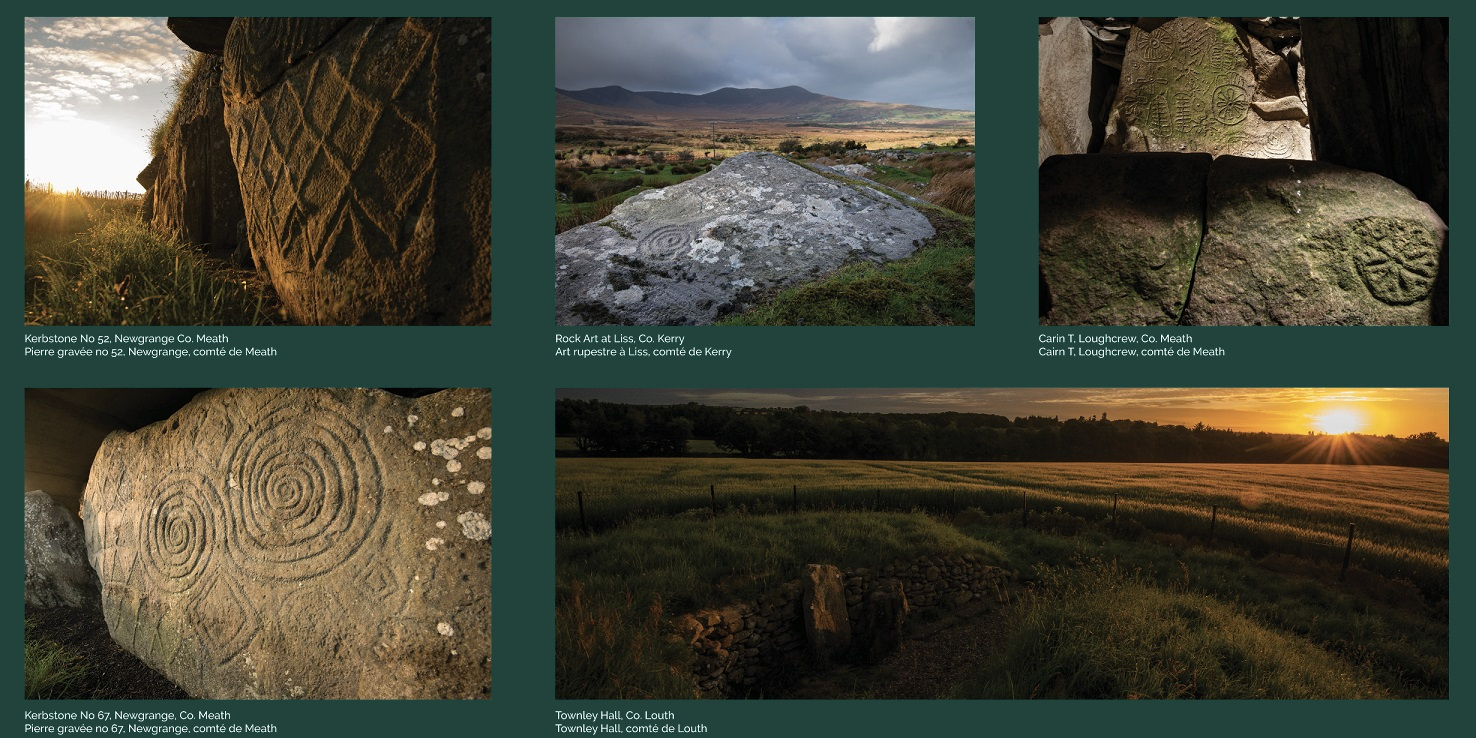

Rock Art at Liss, Co. Kerry

The rugged mountains and valleys of west Kerry are host to the highest concentration of Neolithic carvings in Ireland. The small cup marks enclosed by incised circles are typical of a form of art found on natural outcrops of rock scattered around the open landscape in many parts of Ireland over 5500 years ago.

Cairn T, Loughcrew, Co. Meath.

Kerbstone No 52, Newgrange Co. Meath

Kerbstone No 67, Newgrange Co. Meath

In contrast to the simple cup and rings typical of outdoor rock art, more elaborate forms of carvings are found at the complex architectural monuments known as passage tombs, also constructed during the Neolithic. Such art can be found decorating the megalithic chambers within, such as Cairn T at Loughcrew, as well as the large kerb stones encircling the tombs, such as the evocative abstract and geometric forms found at Newgrange at Brú na Bóinne.

Townley Hall, Co. Louth

Not far from the great passage tombs at Brú na Bóinne is this rather small and unassuming example at Townley Hall. While nearby Newgrange is world renowned for its alignment with the rising sun on the winter solstice, less well-known is the alignment of Townley Hall on the rising sun of the summer solstice.

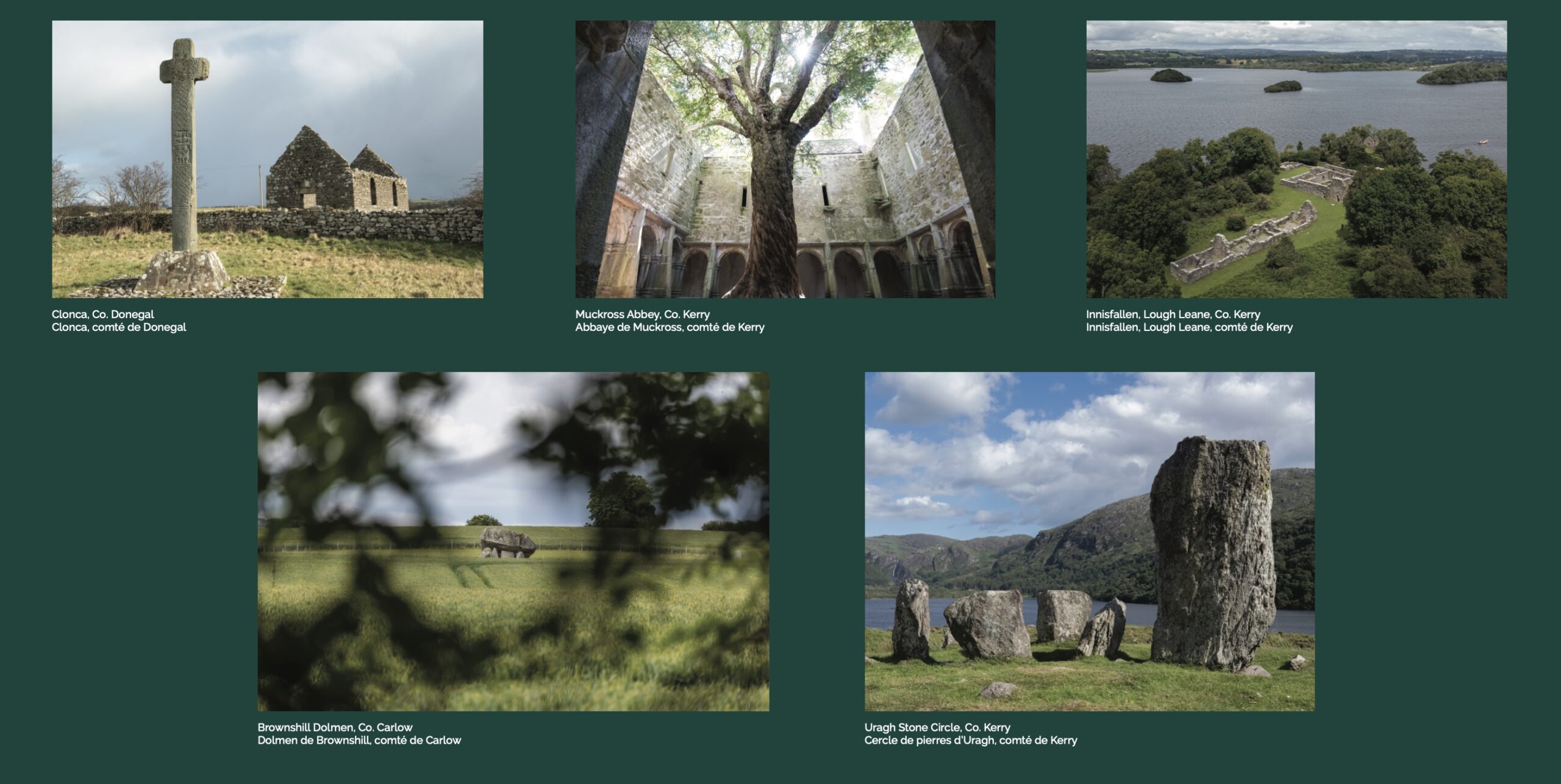

Clonca, Co. Donegal

This tall 9th century cross at Clonca, on the Inishowen Peninsula in north Donegal, marks the site of an early church associated with St Baoithín of Iona in Scotland, which in turn was founded by Donegal’s most famous saint, Colum Cille.

Muckross Abbey, Co. Kerry

Muckross Abbey, on the shores of Lough Leane, was founded around AD1440 by Donal ‘an Daimh’ (the poet) MacCarthy, Gaelic lord of west Kerry. The ruins of the Franciscan friary are remarkably intact and are among the finest preserved remains of a late medieval monastery anywhere in Europe.

Innisfallen, Lough Leane, Co. Kerry

During the 6th century a monastery was reputedly founded by St Finan on the island of Innisfallen on Lough Leane, one of the world renowned Lakes of Killarney. During the 12th century the site became a house of Canons Regular of St Augustine, who transformed the monastery but also retained some of the older churches on the island.

Brownshill Dolmen, Co. Carlow

Known locally as Brownshill dolmen, this portal tomb was built around 3500 BC. The massive granite capstone is reputed to weigh 100 tonnes (100,000kg) and is the largest capstone of any megalithic tomb in Ireland.

Uragh Stone Circle, Co. Kerry

Overlooking Lough Inchiquin and its surrounding mountains in south Kerry, is Uragh stone circle and standing stone, most likely erected around 1500BC. The small ceremonial circle comprises just five stones that are dwarfed by the giant standing stone, some 3m tall.

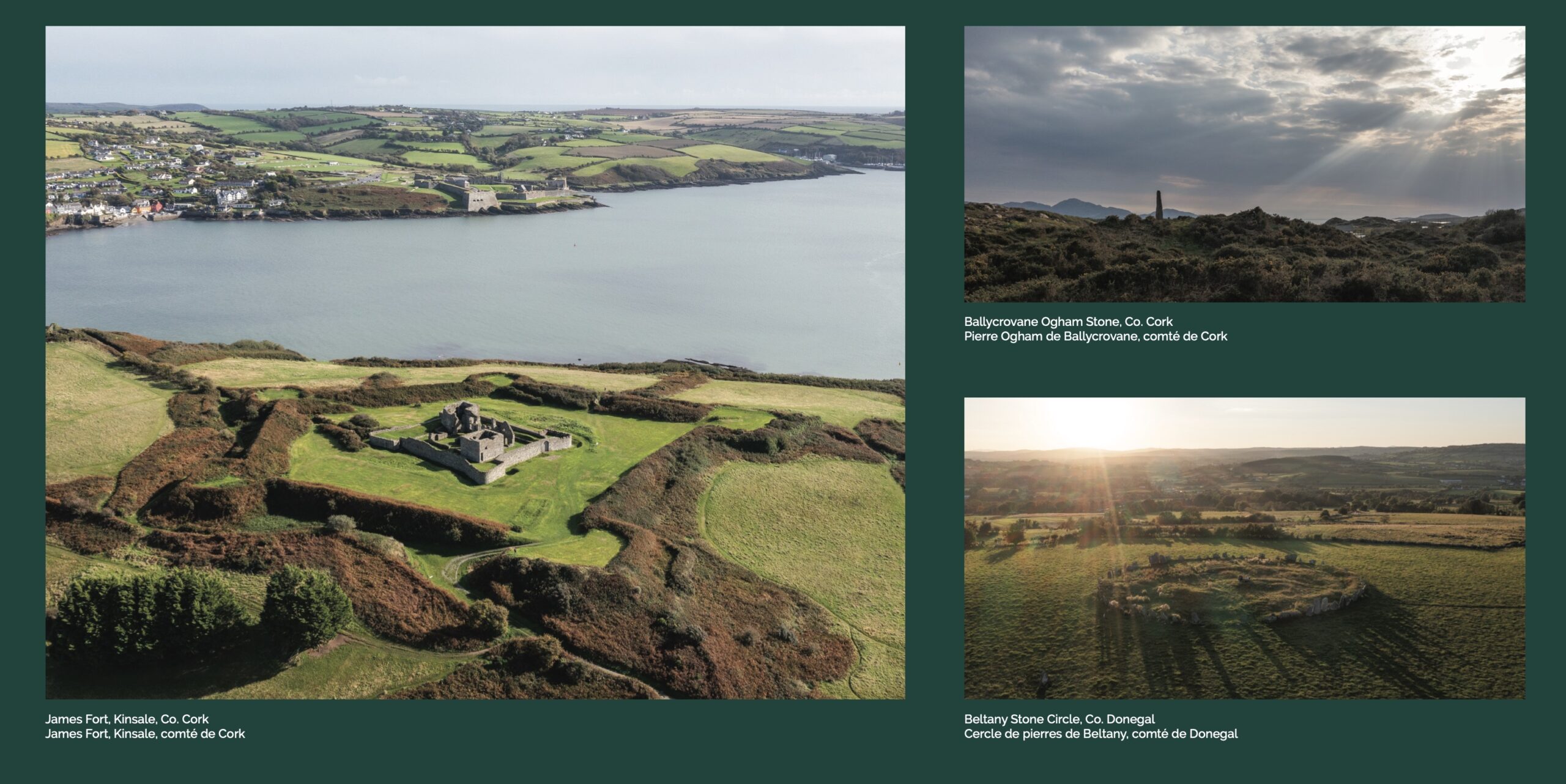

James Fort, Kinsale, Co. Cork

In 1601, a massive army of Spanish troops landed in west Cork at the invitation of Gaelic lords who had mounted a decade-long campaign against English rule in Ireland. This resulted in the Battle of Kinsale, where the English crown forces won a resounding victory that in many ways brought an end to the medieval way of life in Ireland. The English government in Ireland began a swift campaign of defending the south coast with the most modern fortifications. In February 1602, construction began of the pentagonal bastioned fort to defend Kinsale Harbour. The fort was completed in 1604 and was used throughout the 17th century.

Ballycrovane Ogham Stone, Co. Cork

Overlooking Ballycrovane Harbour in west Cork is one of the tallest prehistoric standing stones in Ireland. Nearly 5m tall, it stood in silence for over a thousand years, until an ogham inscription was added along one side of the stone, commemorating the early medieval Uí Thorna rulers of the region.

Beltany Stone Circle, Co. Donegal

Near Raphoe in Donegal is one of the largest stone circles in Ireland, comprising 64 stones arranged in a circle nearly 45m across. Known as the Beltany stone circle, it takes its name from the ancient Irish festival of Bealtaine, at the beginning of May, the traditional start of the Irish summer.

The Rock of Cashel, Co. Tipperary

From the dawn of history, the Rock of Cashel emerged as a symbol of the kingship of Munster until AD1101, when Muirchertach Ua Briain donated the Rock of Cashel to the church ‘as an offering to St Patrick and to the Lord’. Today the rock hosts an early 12th century round tower (a typical Irish belfry), a Romanesque chapel and the finest late medieval cathedral surviving in Ireland. Collectively, these medieval buildings form an iconic and unforgettable profile on the local skyline.

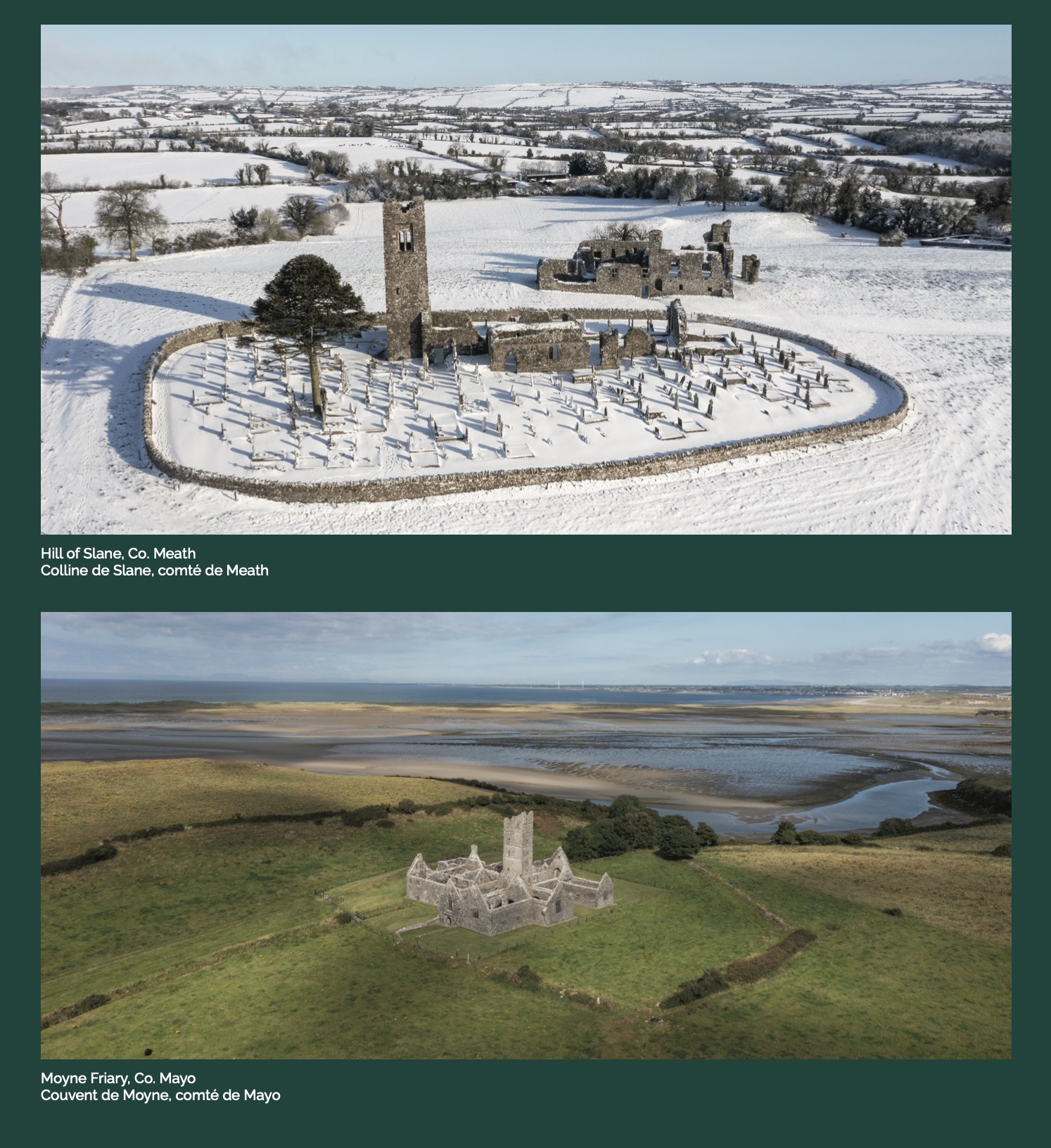

Hill of Slane, Co. Meath

Near the summit of the Hill of Slane are the ruins of a church that was abandoned in 1712, but was originally founded in the late 5th century by St Erc, a follower of St Patrick and one of the earliest Christian missionaries to Ireland. Nearby are the remains of a College of canons, founded in 1512 by Sir Christopher Fleming and his wife Elizabeth Stuckly.

Moyne Friary, Co. Mayo

Situated on the western shores of Killala Bay, Moyne friary was established around 1455 by the Observant order of Franciscans. The complex of buildings now stands in ruins but is otherwise one of the most intact Franciscan friaries anywhere in Europe.

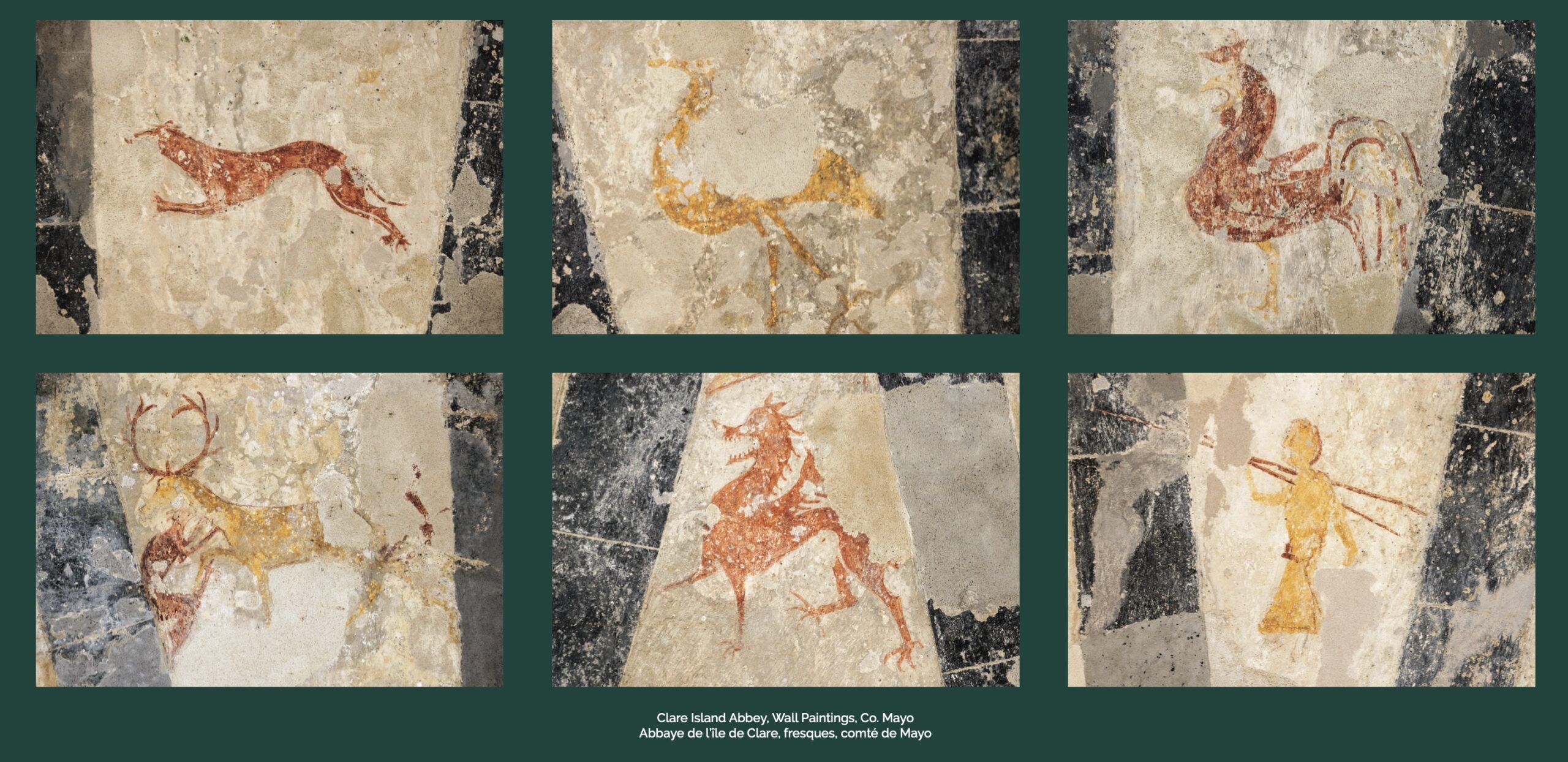

Clare Island Abbey, Wall Paintings, Co. Mayo

Mural paintings were once a common feature of late medieval religious and secular buildings throughout Ireland, but very few have endured the damp Irish climate, which makes the survival of these paintings on a remote Atlantic island even more remarkable. This small church was held by the Cistercian abbey of Abbeyknockmoy, Co. Galway, and was the most westerly Cistercian chapel in late medieval Europe. The vaulted ceiling over the chancel is covered in an unusual variety of painted scenes. While some are obviously religious, others are fantastical, such as a griffin and dragon. There are also hunting scenes, including a stag being attacked by hounds. The stag was seen as an emblem of solitude, purity and nobility, so it is likely that what may initially appear to be a secular image in fact had a deeply religious meaning as a symbol of Christianity’s struggle with evil.

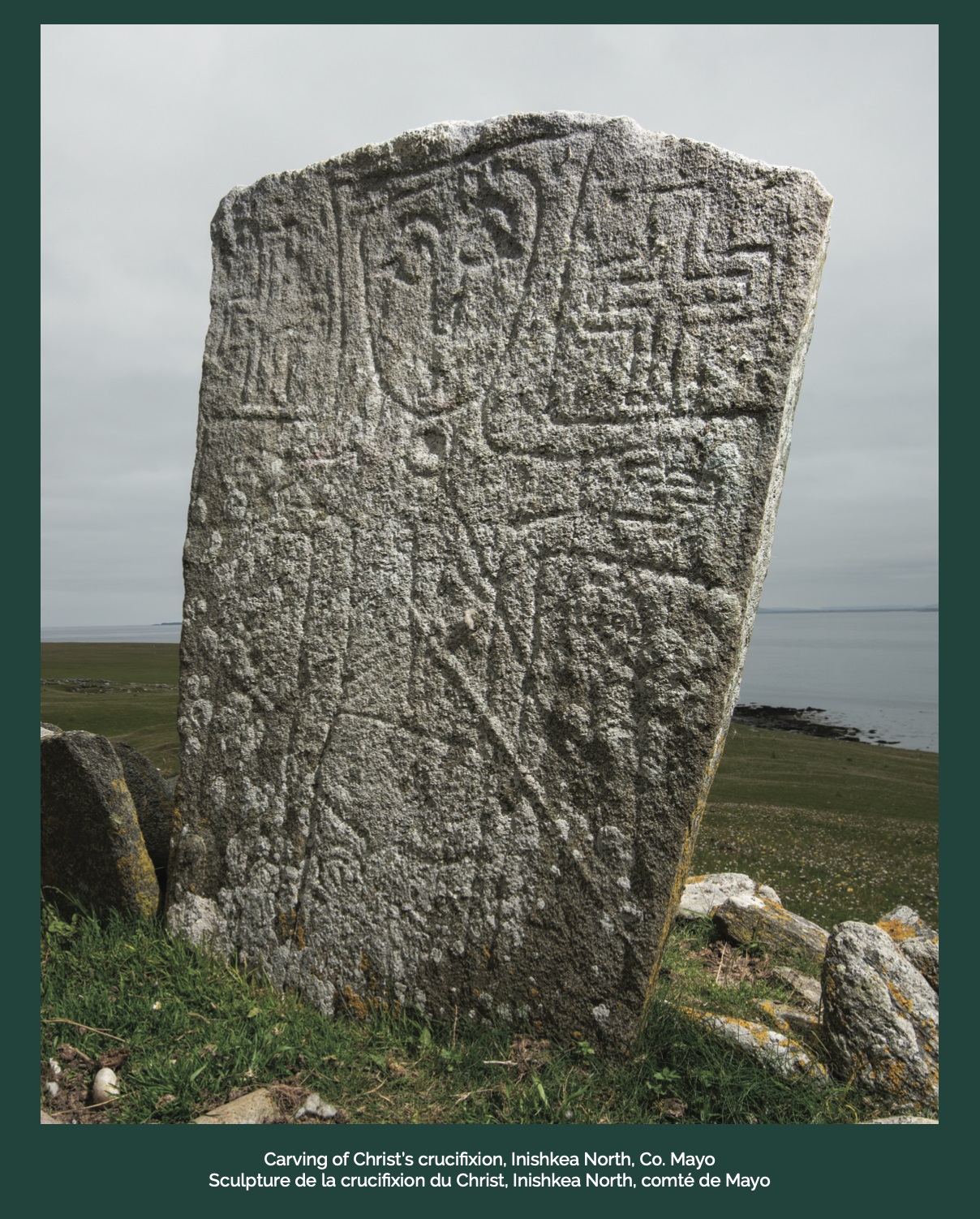

Carving of Christ’s crucifixion, Inishkea North, Co. Mayo

The Inishkeas are amongst the remotest islands off Ireland’s west coast. It was precisely the isolation of these Atlantic islands that attracted a wave of eremitical foundations during the 7th and 8th centuries AD. On the northern of the two Inishkea islands are the remains of a small monastery dedicated to St Columcille, including one of the earliest known Irish carvings of Christ’s crucifixion, likely dating the late 7th century.

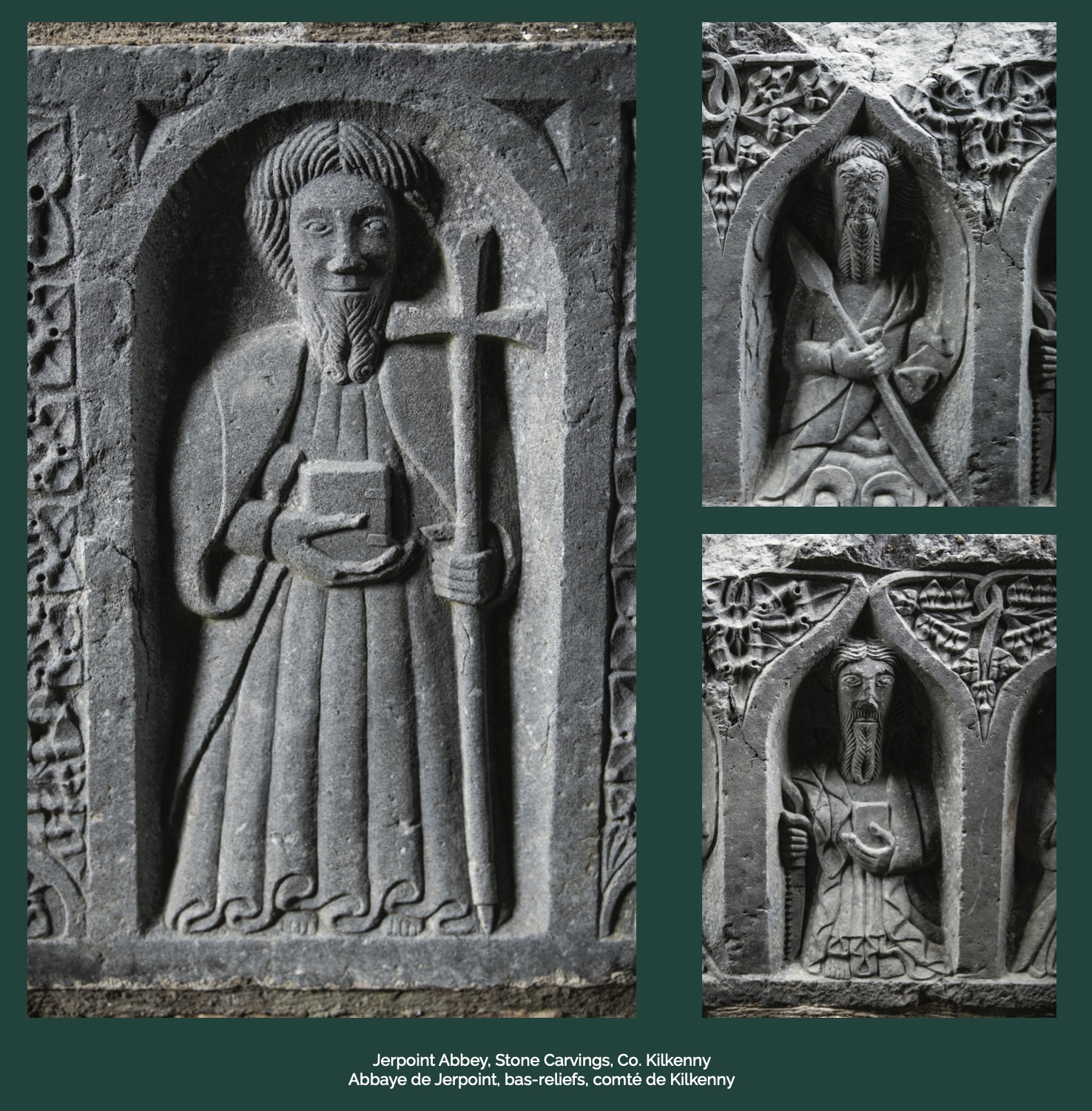

Jerpoint Abbey, Stone Carvings, Co. Kilkenny

These carvings are found on tombs sculpted around the middle of the 16th century by a Kilkenny stone cutter, Rory O’Tunney. The tombs are found within the church of the Cistercian abbey at Jerpoint and the families who commissioned them chose the apostles and saints who were closest to their hearts. Here we see Simon the Zealot and St Thomas holding a saw and spear (symbols of their respective martyrdoms), while the central figure is thought to depict St Jude (Thaddeus).